Home Film My Art

Art

Other: (Travel, Rants, Obits)

Links About

Contact

Stan Brakhage links page Stan Brakhage stills page

This review of the last films completed by Stan Brakhage before his death on March 9, 2003 appeared in the Chicago Reader on May 16, 2003, both the print edition and the Web site, under the title Scenes From the Afterlife. I post it here with a few small additions, and many color frame enlargements. Fred Camper

All images from Brakhage films here are reproduced by permission of the Estate of Stan Brakhage and may not be reproduced elsewhere, including on the Internet, except by permission of Marilyn Brakhage (email her at vams@shaw.ca). Once permission has been arranged, email me for higher resolution files.

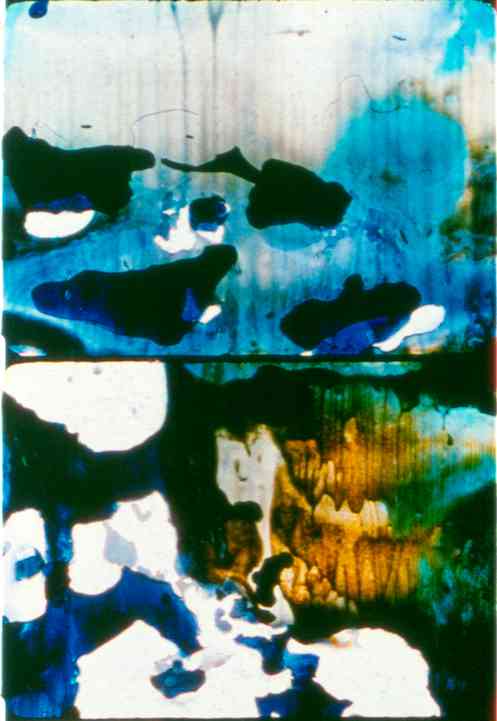

The images below are placed from left to right in the order in which they appear in the film. Note that the strips show more of the image's edges than is seen on the screen; projectors are designed to crop the image slightly, and I replicate the standard degree of cropping when I post single frames. Most importantly, most of the images appear in the films for only 1/12th or 1/24th of a second; at twelve different compositions per second, the eye can't wander around in the richly detailed paintings as it can in stills, and these paintings' fleeting, apparition-like quality and the films' jittery collisions of images are keys to Brakhage's aesthetic.

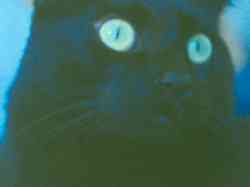

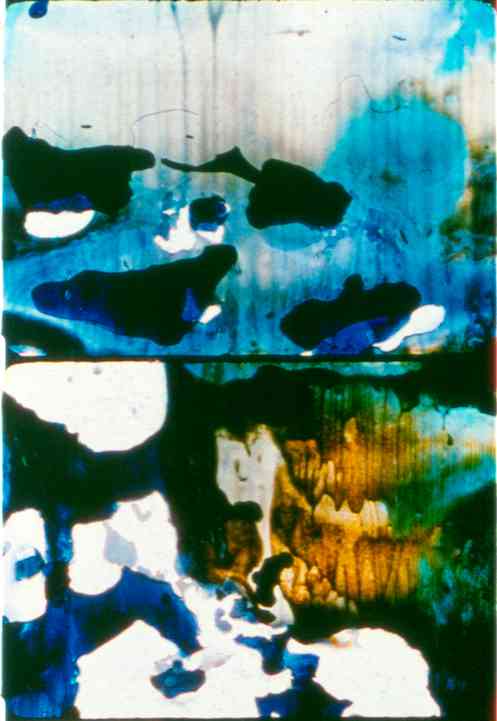

Frame enlargements from Panels for the Walls of Heaven (below) and Max (right), by Stan Brakhage:

A Review of Stan Brakhage's Last Films

By Fred Camper

Last year, after the return

of the cancer that would cost him his life in March, Stan Brakhage told me

in a phone conversation that he'd just completed two films,

Ascension and Resurrectus Est; I knew he was also

working on a longer film, Panels for the Walls of Heaven. Knowing

that he hadn't lost his sense of humor, I said, "Stan, I don't like the

way these titles are sounding. When we talk again, I want to hear that

you're working on a film titled `The Next Ten Years.'" He chuckled, then

said, "The thought of living for another ten years horrifies me." He went

on to say that he'd always been ambivalent about life. While other

evidence suggests that he really did want to go on living, his comment has

resonated with me as a key insight into his career, which spanned 50 years

and close to 400 films.

Brakhage's ambivalence about existence can be seen in his early film

dramas, in which agonized individuals strain against imagined prisons; it

can be seen in his first major work, Anticipation of the Night

(1958), a testament to the failure of imaginative seeing, ending in the

protagonist's suicide; it can be seen in the cosmic deconstruction that

concludes the four-hour The Art of Vision (1965); it can be seen in

what is perhaps his greatest achievement, the "Arabics," a series of 19

abstract films that are both glorious examples of light in motion and

unsettling documents of seeing so "abnormal" that the viewer feels almost

disoriented. And it can be seen in his five final completed works, being

shown at the Film Center May 20 in a "Tribute and Benefit" to assist his family with the

costs of his final illness. Four of the five are Chicago premieres (the

2001 Jesus Trilogy and Coda is not), and this is only their fourth

public showing anywhere. (The two works left unfinished at his death are

being completed by former students and will soon be released.)

Taking defiance of filmic forms to a new extreme, these works have

qualities often found in an artist's late oeuvre. Brakhage refines his art

to its essence, to an unpredictability that's nevertheless not random,

neither borrowing from drama as in his earlier films nor supplying the

potent symbolism of such late hand-painted works as The Dark Tower.

The last four films in particular have an austere, almost autumnal visual

and emotional evenness. All but one of the four — Max is the

exception — were made by painting directly on the 16-millimeter film

strip one frame at a time, and their shifts in perspective keep the viewer

on edge to an almost delirious degree. Because each frame takes only one

twenty-fourth of a second, Brakhage often chose to repeat each one two,

three, or four times in the printing, resulting in between 6 and 12 images

per second. At this speed, each painting is visible just long enough to be

perceived in some detail but not long enough to become a static picture.

The resulting tension between stills and implied movement is only one of

the many ways Brakhage sets the viewer off balance.

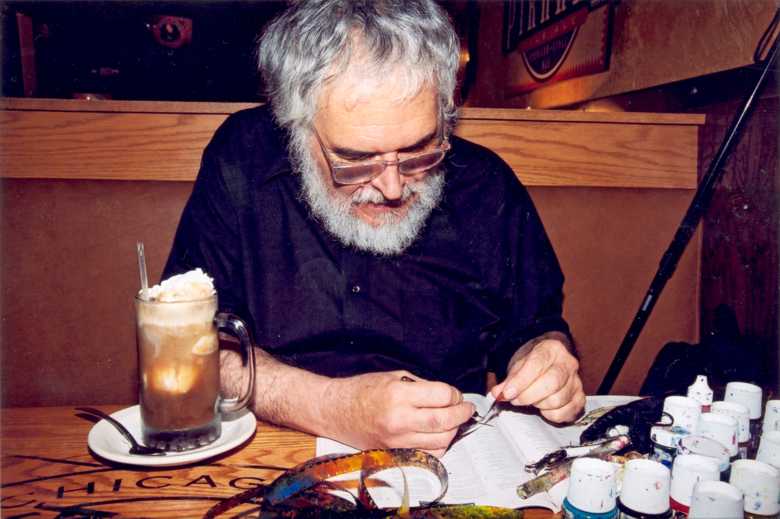

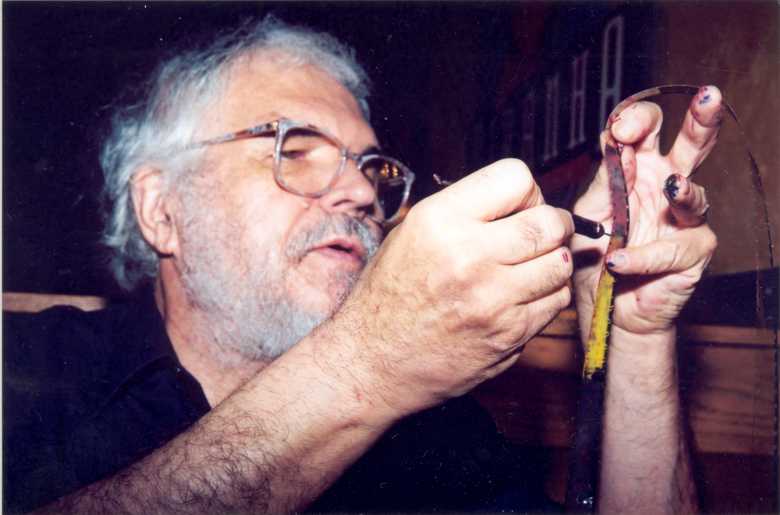

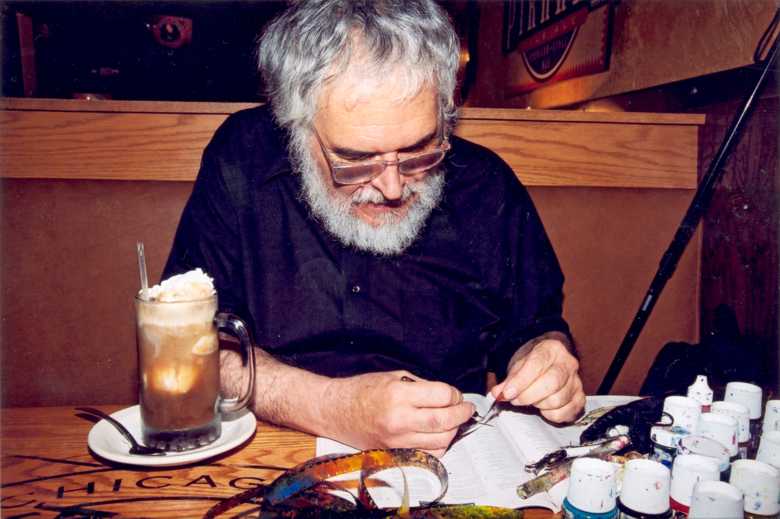

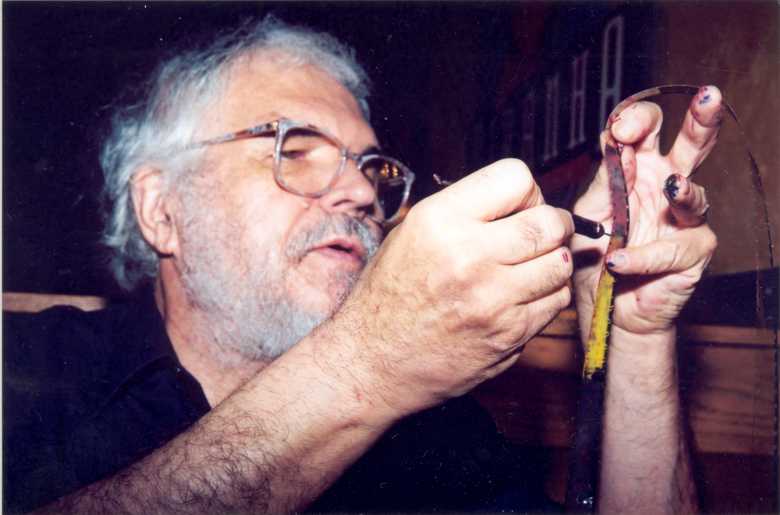

Stan Brakhage painting on film in a Boulder cafe, 2002, photographed by Kai Sibley, copyright © Kai Sibley 2002. If you wish to reproduce these, and other portraits of Brakhage by Kai Sibley that I have available, please write to Kai Sibley. With her permission, I can make larger and higher-resolution versions available for download..

These films are as sensuously spectacular as his previous works,

beautiful accretions of color. Contrasts heighten the impact of each

instant: Brakhage makes a sharply textured red pierce a fuzzier blue

within a composition, in superimposition, or in editing — only one of a

thousand dynamic clashes that intensify our seeing, as if scouring out the

vision. These contrasts give the spectator an active role — each film is

an "adventure in perception," as Brakhage put it at the opening of his book, Metaphors on Visions. His speculation about

the prelinguistic seeing of children is just one example of a more general

interest in alternatives to functional vision, the kind we need in order

to walk across a room without bumping into things. Still in search of

alternatives, these films are if anything more extreme than Brakhage's

earlier work: no single look or rhythm dominates.

Brakhage said late last year that he tried to choose titles to "open

people to seeing the film." Yet the title of the longest film on the

program, the 31-minute Panels for the Walls of Heaven, seems almost

false advertising: it looks nothing like static panel paintings and never

reaches stasis — a major part of its point. More than halfway through the

film an image is held for several seconds, but this is a dynamic event, a

surprise because the picture lasts more than the expected fraction of a

second; significantly, the image Brakhage chooses to hold is mostly

black.

Panels for the Walls of Heaven is the fourth and last of the

"Vancouver Island" films, all of which present Brakhage's imaginary

biography of his second wife, Marilyn. Brakhage said in a videotaped

introduction he made in January for this program that his film does not

aim to be "worthy of heavenliness"; rather, it's an "imagination of same."

And the viewer might be hard-pressed to see any conventional heaven here

— not only are there no recognizable pictures, there isn't even a single

mood. Hating symmetry, avoiding all forms of predictability, Brakhage

produces compositions that are off center, weighted toward one area as if

ready to tip over. And each image does tip over, very rapidly, into the

next, yielding to its successor.

[Frame enlargements from Panels for the Walls of Heaven, by Stan Brakhage. These and the other images on this page appear from left to right in the order in which they appear in the film. For those sections of the film in which each frame is printed two or more times, I've shown only two adjacent frames, to show the cut. For two strips in which every frame is different, I've included three frames. Please also note that the strips show more of the image's edges than is seen on the screen; projectors are designed to crop the image slightly.]

The sheer variety of images in Panels for the Walls of Heaven

creates a labyrinth of possibilities. Spots of color pierce the darkness;

transparent washes are drawn over white as if painted on glass; textures

vary, from areas of color rendered in parallel lines like brush strokes to

soft, even fields to mottled patterns of multiple similar shapes. At times

the texture of the paint is sharply visible, at other times intentionally

thrown out of focus in the printing. There are suggestions of glowing rock

caves, of ice caves, of very near surfaces, and of distant clouds. Often

different types of images are overlaid; superimposing sharp paintings on

out-of-focus ones is particularly striking, suggesting an alternative way

of seeing the sharp ones. And the rhythms of the images vary, from rapid

staccato bursts to continuously dancing forms to sudden decelerations

lasting a mere fraction of a second. Brakhage's imagined heaven is an

unceasing dance with light.

The emphasis on unpredictability prevents the film from having a

readily graspable structure. Instead it lives and breathes in its

instants, as the viewer reinvents seeing at each moment of its unspooling.

Brakhage seeks not spectacular pictures — certainly not to the extent he

did in some earlier work — but constant change, making one question the

very nature of existence. Pushing his films almost to the point of chaos

and denying the viewer images from the world we know, he creates the sense

of teetering on a brink, of consciousness suspended over a void by the

slenderest of threads.

Brakhage achieves an exquisite balance between opposites, between

organizing light over time in a manner worthy of the classical music that

inspired him and pulling apart the raw stuff of the world into near chaos.

More extraordinary, he fuses these opposites: we feel both impulses at

once and experience them as reconciled. Yet freeing vision from cultural

expectations seems to entail abjuring the continuous self, producing a

death song of sorts. Underlying Brakhage's flirtation with chaos is a

philosophical question: How much freedom from convention is it possible to

achieve and still go on living in the world?

[Frame enlargements from Ascension, by Stan Brakhage, in the order in which they appear in the film, starting with the first two images, which are shown in the strip at far left. In these strips, each frame is printed twice, so in showing two different frames I am also showing a "cut."]

The shorter films on the program are no less spectacular or profound.

Ascension begins by superimposing paintings that look like clouds

over extremely close views of mottled paint, peculiarly intimate in their

three-dimensionality. Juxtaposing images of transcendence with

representations of what he liked to call the "mess" of life, Brakhage

distances himself from both.

[Frame enlargements from Resurrectus Est, by Stan Brakhage, in the order in which they appear in the film, starting with the first two images, which are shown in the strip at far left. In these strips, each frame is printed twice, so in showing two different frames I am also showing a "cut."]

In Resurrectus Est, he sets complex

fields of paint and color combinations against a largely white background.

Near the end, the paintings become separated by longer and longer

stretches of white. Brakhage once said he wanted to "leave a snail's trail

in the moonlight," and these splotches of paint against white seem

acknowledgments of a certain humility new to him.

[Frame enlargements from Max, by Stan Brakhage. The strip at left is from near the film's opening; at right, from near the very end.]

The one work made with a movie camera, Max, grew out of

Brakhage's desire to create a record of his cat. After several attempts,

he was finally satisfied with a single roll, edited in camera. He used to

complain that viewers didn't understand that he had a sense of humor, but

often his humor is subtle, revolving around individual oddities, whether

of humans or animals — a body or face or eye that stands out from a more

even field of light. Because for Brakhage light stands for the energy

underlying all things, sometimes it seems that locking it into a

recognizable or namable shape is too restrictive. Max jokes about

this issue by making the cat's individuality seem odd, as its bright eyes

occasionally peer out from a mass of soft-focus fur, markers of a being

that almost seems to understand its own insignificance.

Best known as an advocate of individual vision in film, Brakhage by the

middle of his career was starting to shift his definition of self away

from "personality" and toward a more expansive sort of consciousness. At the film's beginning, Max appears out of the yellow-red flares that are caused by light fogging at the beginnings and ends of film rolls; at the end, Max vanishes into those same flares, so that her presence is subsumed by a yellowish fog. Though this effect is often seen in single camera roll films, here it combines with the oddness of Max's presence and the delicacy of Brakhage's compositions to make a point about the fragility and temporariness of the film image, about its roots in pure light. And at the end, it seems as if the filmmaker uses the cinematic process to say good-bye to us — and to all the things of this world.

Goodbye, Stan.

Copyright © Fred Camper 2003

All images from Brakhage films here are reproduced by permission of the Estate of Stan Brakhage and may not be reproduced elsewhere, including on the Internet, except by permission of Marilyn Brakhage (email her at vams@shaw.ca). Once permission has been arranged, email me for higher resolution files.

Stan Brakhage's films are available for rental

from the Film-Makers' Cooperative, Canyon Cinema, and other distributors.

Chicago Reader Links:

Reader Homepage |

On Film Main Screen |

Archive of Long Reviews |

Archive of Brief Reviews |

Critic's Choices |

Showtimes |

Stan Brakhage links page Stan Brakhage stills page

Home Film My Art

Art

Other: (Travel, Rants, Obits)

Links About

Contact